Bottleneck at Patent Office is Leading Indicator of U.S. Economy

1.2 million patents waiting; it takes 34 months for patents to be issued; American innovation and competitiveness at risk and American jobs not being createdA few months ago I was taking a free class on living off grid where I met an examiner with the U.S. Patent Office for about 25 years. I mentioned to him that I heard there was a backlog in applications, which he confirmed. When I asked him why this was so, he told me that about 15 years ago the examiners where instructed by management to intentionally slow down the processing of applications because the U.S. government was using patent revenue for other purposes. He also mentioned that examiner attrition is high because law firms recruit former examiners so that they can have inside contacts to help expedite patent applications of their clients.

The number of applications for U.S. patents has increased every year for 20 years. The number of patent examiners has not kept pace, and now over one million patents are waiting to be examined. [Patent Backlog Grows to Record Levels, Impact Lab, August 31, 2006]

If there is a problem with the patent system, it is not that patents are issued too hastily, but rather that many are issued too slowly. Witness the current backlog and pendency. In some sections at the Patent Office it takes three years or more just to get a first office action. With this kind of pendency, by the time an inventor gets their patent, their technology is of no value. If small entities can't get timely patents, we can't get funded. If we can't get funded, promising new discoveries will die on the vine. That is the problem everyone should be focused on — not this imaginary issue of patent quality trumpeted by large multinationals as a way to stifle innovation and further cement their market control. There is then no systematic abuse of the patent system by patentees which would require an overhaul of the system. To the contrary, there is a reason why the patent system works the way it does. We didn't get here by accident. That's because of past abuse of the system by large companies who used their wealth and power to give small entities the run around and make a sham of the system. [Professional Inventors Alliance]

Bloomberg Interview of David Kappos, Former IBM Executive and New Director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office:

Patent Office Reforms Derailed

Milwaukee Wisconsin Journal SentinelApril 25, 2011

Reacting to Congress' decision to raid another $100 million from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, the agency's director has thrown the brakes on nearly every one of its planned internal reforms, triggering new warnings that the congressional action will cause a "catastrophic" setback for American innovation, competitiveness and job creation.

"It's a tax imposed on innovators," said Paul Michel, recently retired chief justice of the federal court in Washington, D.C., that handles patent cases.

Because the patent office is structured to be self-supporting by charging fees without costing taxpayers a penny, Congress effectively has helped itself to funds that belong to garage entrepreneurs, start-ups and inventors, Michel said Monday.

"Instead of helping innovators by speeding the patent system, Congress is impeding innovators by taxing their innovations," he said.As reported in a series of stories in the Journal Sentinel since 2009, the patent office has struggled for years to keep up with the burgeoning number and complexity of patent applications it receives. Crippled by the ongoing series of raids on its fees dating to the early 1990s, it has fallen desperately behind and now has a backlog of more than 1.2 million applications awaiting a final decision - nearly tripled from about 10 years ago.

Patent office director David Kappos, a former IBM executive who was appointed less than two years ago to turn around the agency, late last week sent a memo to his examiners that "reluctantly" details how the latest congressional budget actions will cripple his efforts:

- He indefinitely postponed a pilot program that guarantees fast-track examination of applications within a year to those who pay an additional fee. The program would have gone into effect next week.

- For the second time since he took over, Kappos imposed a hiring freeze at the chronically understaffed agency. Since 2005, the patent office has aimed to hire 1,300 new examiners each year just to chip away at the backlog. But with deficits of nearly $1 million per working day, it hires only sporadically at best.

- The agency suspended all overtime - halting one of the few approaches at its disposal to eat into its backlog - and slashed the training budget for new examiners, who typically need three years to gain competence.

- Plans to open the agency's first satellite office, in Detroit, meant to ease overcrowding at its campus outside Washington, have been "postponed until further notice."

- Upgrades to the agency's antiquated and dysfunctional computer system will be cut to "mission critical" upgrades only.

"We have not come by these decisions easily," Kappos wrote. "I recognize that these measures will place additional burdens on your offices, your staff, and your ability to carry out the agency's mission."Legislators siphoned the funds as part of the emergency spending bill to avert a shutdown of the federal government this month.

"I see a negative impact on pendency (the length of time required to get a patent) and backlog," said Barry Grossman, a senior patent attorney in Milwaukee at the Foley & Lardner law firm. "The program reductions will not promote technological progress and innovation, nor will they reduce pendency, reduce the backlog or improve quality."According to a Journal Sentinel analysis, patents awarded by the agency last year took nearly four years from application to issuance, on average - more than twice the agency's benchmark of 18 months.

Because more than a half-million new applications arrive every year - the number rises each year - the office has been unable to catch up. Under a best-case scenario made before the latest congressional raid, Kappos predicted that the agency could reduce its backlog to manageable levels by 2015.

While Beijing invests heavily in China's patent system - now the world's third-biggest, behind the United States and Japan - American innovation activists decry Washington's divestment in the U.S. patent system. The patent system has always been linked to the American dream: The issuance of single patents launched IBM, General Electric and Johnson Controls, not to mention much of Silicon Valley as well as Madison's biotech economy."There is no great surprise why we are having a jobless recovery," said Eugene Quinn, a Washington, D.C.-area patent attorney and author of the IPWatchdog.com blog.Washington's policy-makers appear oblivious to the importance of intellectual property and the historical role that the patent system plays in the nation's economy, Quinn wrote in reaction to the latest diversion. "The PTO has to throw up its hands and cease trying to make progress, treading water at best, but more likely drowning," Quinn wrote. "Pathetic."

The latest diversion comes as key Senate and House leaders as well as the White House have started to extol the importance of the agency. President Barack Obama and his advisers have vowed to strengthen the nation's innovation economy, and Commerce Secretary Gary Locke used an appearance in Milwaukee this month to tout the fast-track examination system.

Pending legislation called the America Invents Act of 2011 deals largely with patent litigation but also includes a provision to allow the patent office to keep its fees. Yet even if Congress passes the legislation - it has rejected three previous attempts over the past four years - the agency wouldn't gain control over its finances until the new fiscal year starts Oct. 1.Michel, the former patent court judge, called the latest diversion "catastrophic and devastating."

Michel noted that small companies and start-ups create the bulk of new jobs in the U.S. economy, and those are the entities hardest hit by a dysfunctional patent office.

"The delays in the patent office are already the biggest problem in the American patent system," Michel said, "and they are holding back new companies, new technologies and new jobs."

Patent Backlog Clogs Recovery

Agency’s inability to keep pace undermines American innovation, competitivenessMilwaukee Wisconsin Journal Sentinel

First of two parts

On a campus of boxy office buildings nine miles outside Washington, D.C., some 6,300 patent examiners hold the nation's economic future in their hands.

The next Google. The next iPhone. The next Viagra.

All could be fueled by inventions awaiting the 20 years of protection afforded by a U.S. patent - if only the patent examiners could catch up.

But they can't. The federal system of granting patents to businesses and entrepreneurs has become overwhelmed by the growing volume and complexity of the applications it receives, creating a massive backlog that by its own reckoning could take at least six years to get under control, the Journal Sentinel has found.

Amid the worst downturn since the Great Depression, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office could be seen as a way to jump-start the economy. Instead, it sits on applications for years, placing inventors at risk of losing their ideas to savvy competitors at home and abroad.

The agency took 3.5 years, on average, for each patent it issued in 2008, a Journal Sentinel analysis of patent data shows. That's more than twice the agency's benchmark of 18 months to deal with a patent request.

The total number of applications waiting for approval, more than 1.2 million, nearly tripled from 10 years earlier.

The Journal Sentinel also found:

- Under a practice that Congress authorized a decade ago, the Patent Office publishes applications on its Web site 18 months after the inventor files them, outlining each innovation in detail regardless of whether an examiner has begun considering the application. The system invites competitors anywhere in the world to steal ideas.

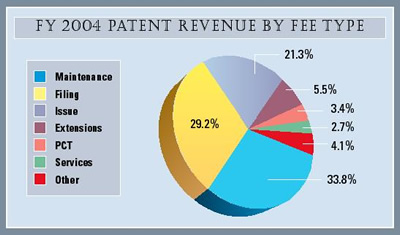

- For more than a dozen years starting in 1992, Congress siphoned off a total of $752 million in fees from the Patent Office to pay for unrelated federal projects, decimating the agency's ability to hire and train new examiners.

- As its backlog grew, the Patent Office began rejecting applications at an unprecedented pace. Where seven of 10 applications led to patents less than a decade ago, fewer than half are approved today - a shift that a federal appeals judge termed "suspicious." The same judge calls the agency "practically dysfunctional."

- Staff turnover has become epidemic. Experts say it takes at least three years for a patent examiner to gain competence, and yet one examiner has been quitting on average for every two the agency hires.

- Patent activity, a widely accepted barometer of innovation, is showing exponential growth in increasingly competitive economies such as China, South Korea and India. As developing economies strive to commercialize and protect their technologies throughout the world, they add tremendously to the U.S. Patent Office's workload.

- In many cases, applications languish so long that the technology they seek to protect becomes obsolete, or a product loses the interest of investors who could give it a chance at commercial success. "Patents are becoming commercially irrelevant to product life cycles," said John White, a patent attorney and former examiner.

For an American start-up company, a patent application is often the only asset, which creates a Catch-22: Start-ups often need a patent in order to get funding; yet without that funding, entrepreneurs can't afford the mounting fees and legal costs to keep the patent application alive or to fend off infringers.

Backlog hits homeJust such a delay doomed MatriLab Inc., a Milwaukee biotech company formed to commercialize a wound-healing gel based on technology licensed from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Backed initially by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, which works to commercialize UW technologies, MatriLab won the governor's business plan contest in 2006. It went belly up in 2007, five years after a patent application was filed for the gel, because no new investors would come aboard as the application languished.

"The absence of patent protection says to investors, 'Maybe these people really don't have anything,'" said Grady Frenchick, a veteran patent attorney in Madison with Whyte Hirschboeck Dudek, who represented MatriLab.

Kathleen Kelleher, chief executive of the short-lived start-up, went on a 20-stop investor roadshow. But without a patent in hand, she couldn't raise a penny.

"Potential investors want to know if there will be some level of exclusivity or protection," said Kelleher, whose résumé includes 25 years in the biotech industry.

A patent was finally awarded for the compound this year; it went to WARF, which reclaimed its license when MatriLab ran out of cash.

MatriLab ended with nothing.

"That story is retold across the country thousands of times," said White, who also teaches patent law. "People give up on their dreams."

Patent delays buried Merc-Exchange LLC, a Virginia company that survived several costly court battles with eBay but couldn't outlast the Patent Office.

In 2003, a federal court found that eBay was infringing on MercExchange's patented online-auction technology - so eBay asked the Patent Office to re-examine the two most crucial patents in an effort to invalidate them.

The agency reopened the examination in March 2004. Four years later, with the validity of his patents still in limbo, MercExchange founder Thomas Woolston capitulated and sold them to eBay.

"It destroyed us," Woolston said.

MercExchange went from more than 40 programmers and engineers at its peak to zero.

Of 1,349 patents issued to Wisconsin inventors last year, 123 took at least five years to issue, with some taking as long as nine years, the newspaper's analysis found.

The delays grew beyond frustrating for Roger Hoffman, a Green Bay businessman and inventor whose advances in environmental technology for the paper industry earned him an award from the White House in 1991.

In 2001, he created an Internet-based technology that would allow companies to streamline the process of gathering bids from suppliers. By the time he got his patent more than five years later, the idea had been published online, copied and developed many times over - all technically legal as long as there was no patent. It was rendered worthless to Hoffman, even though the patent he eventually won validated that he was first with the idea.

"You just cannot get anything through the patent office," Hoffman said. "You cannot find investors that will wait eight years for patents to issue. Start-ups are risky enough without that."Set up in Constitution

Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution created the Patent Office.

"The issuing of patents for new discoveries has given a spring of invention beyond my conception," wrote Thomas Jefferson, the nation's first patent examiner.

The patent system encouraged a mechanical engineer named Herman Hollerith to patent a punch-card tabulation machine in 1889 (U.S. patent No. 395,781), prompting him to found the Tabulating Machine Co., which later became IBM Corp. In 1883, Warren Johnson patented the electric thermostat (No. 299,552) and spawned Wisconsin's biggest company, Johnson Controls Inc., with $38 billion in 2008 sales.

Thomas Edison's incandescent light bulb (No. 223,898) launched the General Electric Co. In turn, GE used the vacuum tubes for Edison's filaments to patent vacuum tubes for X-ray equipment (No. 1,203,495). By 1947, GE's X-ray division in Milwaukee was on its way to becoming GE's $17 billion-a-year medical technologies business - which today ranks among Wisconsin's most active users of the patent office.

But over the years, the agency became a backwater, staffers say. The State Department passed it to the Department of the Interior, which handed it off in 1925 to the Commerce Department, where it resides today. It became the registration agency for trademarks, a smaller and separate part of its work.

"Since the '60s, there's an under-appreciation of the importance of the Patent Office to our whole economy, to employment, to prosperity," said Paul Michel, chief justice of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which handles patent appeals. "It's been neglected by the Congress and most high-level policy-makers."

The last time the Patent Office met its 18-month average for passing judgment on applications was 1991 - shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall inaugurated the era of raw global competition.

Funding siphoned offThen in 1992, Congress began siphoning off the agency's revenue.

The Patent Office is structured to be self-sustaining, surviving on fees paid by patent applicants. Facing shortfalls in other areas, however, Congress voted to divert $8 million in fees in 1992 - less than 1% of the agency's budget that year - to pay for federal projects that had nothing to do with patents.

That diversion eventually snowballed into $752 million during the next 12 years, as Congress drained anywhere from $12 million to $200 million each year, regardless of which party controlled Congress or the White House. The diversion amounted to about 7% of the total funding available to the agency during the period of diversion, according to a 2005 report by the National Academy of Public Administration.

"If we had hired an additional 250 to 300 people each year through those years, over what we hired, we'd be at 18 months right now," said John Doll, the Patent Office's acting director until the Senate confirmed IBM executive David Kappos as the agency's new leader on Aug. 7.

As the diversions took their toll and technology competition went global, the Patent Office steadily fell behind. Its backlog of unexamined applications has increased every year since 1997 and now numbers more than 1.2 million, higher than that of any other patent agency in the world.

The diversions ended in 2004, although Congress never legislated a ban on them, and the agency began a game of catch-up, hiring nearly 1,000 new examiners in one year. From 2006 through 2008, it hired and trained at the unprecedented pace of 1,200 examiners a year. In 2006, it opened a Patent Academy with an eight-month curriculum.

It planned to hire another 1,200 each year through 2012 but this year slammed on the brakes with a hiring freeze.

"We don't have the money to hire 1,200 new examiners this year, so we won't be able to make the gains that we expected to make," Doll said.

The agency blames the slowing economy for the drop in its fee income, citing a dip in filings - as companies have reduced research-and-development budgets - and less willingness by inventors to pay the periodic maintenance fees that keep a patent alive for its full term.

In his July 29 Senate confirmation hearing, Kappos said his No. 1 priority is to shorten the amount of time it takes to get a patent without sacrificing quality.

"The challenge of fee diversion has been costly in terms of user-community confidence," Kappos told the senators.

Even so, few expect change to come quickly. Under one internal model, Doll said the agency won't catch up with its workload for a half dozen years. He cited a projection based on a fresh infusion of funding, which would allow the agency to increase the pace of hiring to 1,500 examiners per year. That would drop the average waiting time for a patent to 18.7 months by 2015, Doll said.

Previous efforts to expedite applications had little impact. Three years ago, Doll introduced a program called Accelerated Examination, which is meant to render a decision within 12 months. Only a fraction of applicants use it, patent attorneys say, because it saddles users with extra costs and can create a legal liability that can invalidate patents in court.

Limited impactMost patents have little or no economic impact. An estimate published in 1997 in Research-Technology Management, a business journal, found that only 5% to 10% of U.S. patents have potential market relevance. But that includes those with the potency to build and help maintain the U.S. economy. These represent advances in science, technology and human creativity, from Robert Fulton's steamboat to Orville and Wilbur Wright's flying machine to Google's search engine.

A 2005 Federal Reserve Bank study found that the largest factor in a state's income growth is the volume of patents each state generates. Ranked by patents per capita, Wisconsin is 12% above the national average and 14th nationally.

The system amounts to a social compact: A patent shares advances in science and technology with the world in return for a temporary, exclusive right to make and sell something. A good patent delineates the exact limits of what an inventor wants to protect, which in turn fires the ingenuity of others to improve on it without encroaching. And the system influences every niche of the economy, from manufacturing to stem cells.

Patents "are essential instruments for an innovation-based economy," said Bruce Lehman, director of the Patent Office in the mid-1990s. Neither Silicon Valley nor the Madison biotechnology industry would exist without patent protection, said Lehman, who earned his undergraduate and law degrees from UW-Madison. "To advance science in a market economy, you have to have a system that permits you to capture property rights in inventions so investors will invest and the public gets the benefit," Lehman said.

Yet the U.S. patent system has bogged down just as other fast-developing economies, such as China and India, have ratcheted up their efforts to innovate - and to protect their inventions. And because a patent carries legal force only in the nation that issued it, foreign inventors have added increasingly to the burden at the U.S. Patent Office.

"We're going to see more patent applications from China and the rest of the world, and we cannot hire our way out of it," said Jon Dudas, who ran the U.S. Patent Office from 2004 until earlier this year.

In 2008, about 49% of U.S. patent filings came from foreign inventors, mainly Japan, South Korea and Europe. Last year, for the first time in the agency's history, the Patent Office issued more patents to foreign inventors (80,271) than to U.S. innovators (77,501).

China accounts for less than 1% of U.S. applications. But many expect that to change. The State Intellectual Property Office, China's patent agency, overtook Europe's 35-nation patent office in 2004 to become the world's third-biggest, behind the U.S. and Japan. Applications to the Chinese office tripled to 289,838 in 2008 from 2003, about half from foreign interests, mirroring U.S. trends.

"China has a national plan to be a leader in the world, from 'made in China' to 'invented in China,'" said Dudas, now an attorney in the Washington office of Milwaukee-based Foley & Lardner.

Long waits for patents are not unique to the United States. The European Patent Office takes longer than the United States, on average, to resolve patent applications. The wait in Japan is similar to that in the U.S.

But nowhere do the delays take a greater toll.

Garage entrepreneurialism, the type that created Hewlett-Packard and Harley-Davidson, is more influential in the United States than in most other countries, said Lehman, the former Patent Office director.

"Investments in technology in the United States are to a much greater extent than elsewhere financed by venture capitalists, who require the certainty of patent protection as a precondition," he wrote this year in a policy paper. "Companies like Google didn't exist 10 years ago."Inventor scales back

Born in Two Rivers and educated in chemical engineering at UW-Madison, Roger Hoffman is a compulsive inventor.

During 25 years at Green Bay Packaging Inc. and later as the operator of an independent inventing shop, he created and patented dozens of technologies, many of them dealing with paper industry issues: paper production, recycling and water treatment. In 1991, the first President George Bush honored him with an environmental award in a Rose Garden ceremony.

But now, at age 65, Hoffman splits his time between homes in Wisconsin and Florida, having closed his Green Bay shop in 2003 and gone into semi-retirement because it had become so difficult to get its inventions patented.

"I'd still be in Green Bay if it weren't for the futility of trying to get these patents," he said.

Case in point: In 2001, before many Internet business applications existed, Hoffman created an automated online program that allows a company to collect bids from suppliers around the world, sort through them, determine which ones have the capacity to meet production and delivery specifications, and generate a list of optimal candidates.

This "Decision Analysis System" could work for manufacturers or retailers, whether they needed brake parts, paper pulp or running shoes.

The Patent Office agreed the idea was original and deserved patent protection - more than five years later. By then, the idea had been published on the Patent Office Web site and untold imitators had sprung up.

"Everyone has software products that do what Roger invented years ago," said Philip Weiss, Hoffman's patent attorney. "But if you go back to 2001, there was no such thing."

Hoffman got U.S. Patent No. 7,110,990 for his program in September 2006, proving he was first with the idea. He could have sued some of those who had been duplicating his work, but the technology had quickly become ubiquitous, and patent suits are expensive - pursuing a single infringer can cost $1 million to $5 million.

"Roger never got into this to be a litigator, that I can tell you," Weiss said. "He thought inventors were noble."Hoffman finds it ironic that the building that used to house his eight-person inventing shop in Green Bay is now a courthouse.

"If we had the same system 140 years ago, which was the year Thomas Edison's first patent issued, we probably would not know who Thomas Edison was," Hoffman said.

Working for the USPTO (Excerpt)

On a survey of 1,420 patent examiners. Not surprisingly, the GAO report provides ample support for POPA's position that the USPTO's antiquated production goals are the reason for the Patent Office's high examiner attrition rate (the GAO reports that from 2002 to 2006, one patent examiner left the USPTO for nearly every two the Office hired). Among the specific findings of the GAO survey were:- 67% of the examiners surveyed said that the Patent Office's production goals were among the primary reasons they would consider leaving the USPTO.

- 62% of the examiners surveyed are very dissatisfied or generally dissatisfied with the time the USPTO allots to achieve their production goals.

- 50% of the examiners surveyed are very dissatisfied or generally dissatisfied with how the agency calculates production goals.

- 59% of the examiners surveyed believed that the production system should be reevaluated.

- 70% of the examiners surveyed reported working unpaid overtime during the past year in order to meet their production goals (some putting in more than 15 hours of unpaid overtime per week).

- 59% of the examiners surveyed identified the amount of unpaid overtime that they have to put in to meet their production goals as a primary reason they would choose to leave the USPTO.

- 37% of the examiners surveyed identified the amount of time they must work during paid leave in order to meet their goals as a primary reason they would choose to leave the USPTO.

She also stated that even if the Office were to satisfy its hiring estimate of 1,200 examiners in each of the next five years, the backlog would grow from about 730,000 applications in 2006 to 1.3 million applications in 2011.

Working for the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)

United States Patent and Trademark OfficeMarch 15, 2008

Did you know?

Your career as a Patent Examiner is just beginning – and there’s nowhere to go but up. Do you know about all the opportunity your future at the USPTO holds? Did you know that a primary examiner makes between $102,000 - $145,000 a year? And you can be a primary examiner within only 5-7 years of joining the USPTO? Your career path doesn’t stop there.

You could be a manager, running a group of examiners, after only 7-8 years. All patent managers – all the way up to the Commissioner – started their USPTO careers as patent examiners. Promotions are based on how well you perform relative to a fixed goal – not competition amongst employees. Employees are eligible for their first promotion after only 6 months of employment.

Did you know that as a new employee, you have an immediate impact on the U.S. economy through your own decisions? It’s important work with an important mission. Experienced USPTO employees describe themselves as independent thinkers, disciplined, decisive, self-starters.

How did you hear about careers with the USPTO?

Did you know that word-of-mouth is the main way we recruit new employees?Nearly 40% of patent examiners were hired in FY 2006 by employee referrals. Patent examiners are invaluable – over 450,000 patent applications are filled each year – that means an average examiner will examine 100 patent applications per year. After mastering patent examining, there are other career options for you within the patent office. From being an Administrative Patent Judge at the Board of Appeals, to working on national and international endeavors, and more, the possibilities are as wide as the ideas you’ll work with every day.

If everything is so crappy at the PTO, and everyone hates it there, then why are nearly 40% of patent examiners were hired in FY 2006 by employee referrals (the above article was published in July of 2007)?

From Intellectual Property Law Server:

I was one of the 14 to be hired as a biotech examiner in '97. How did I get the job? I don't have the slightest idea. Nonetheless, here are a few pointers you might want to consider:

Although there is no shortage of new applicants, the PTO has a problem retaining experienced Examiners. Once examiners get their training, they often leave for higher paying (or equally paying, but less stressful) jobs. In fact, many leave leave after just 1 year, and the majority leave within 2 or 3 years.

So without being too overt about it, present yourself as someone who will be around for longer than that. (But don't over do it by claiming that you plan to become a career examiner. The interviewer will think you are lying or aren't very ambitious.) And before you interview, you should also do considerable homework as to what an examiner actually does. You'll need to explain why you want to leave the lab to do this sort of work. You might even want to learn a little patent law so you can "talk the talk" during your interview.

If you haven't already done so, have a look at the MPEP. You might even want to read chapters 700 and 2100 (or parts thereof) just to get a feel for it. Have a look here...

Manual of Patent Examining Procedure" Edition 8 (E8), August 2001, Last Revision July 2010

Hope the above helps.

Compact Prosecution

By Patent Hawk, The Patent OfficeDecember 14, 2007

Unable to staff its way out of its pendency hole, USPTO management seeks to address the problem by limiting continuations and RCEs. Seeking to gratify a grotesque bias, Ayal Sharon & Yifan Liu set out to statistically validate that conclusion. Instead, they proved what many prosecutors already knew: examiners' refusal to grant deserved patents. The root of the problem is a culture now steeped in political fear of being considered slack by granting junk patents, inspired by a short-sighted and incompetent management responding to pressure from well-funded propagandists.

Patent Applications Backed Up: So Are New Jobs

By Myra Per-Lee, InventorSpot.comManufacturing as percent of total employment: via Economist View

Switzerland slid past the U.S. to first place in the 2009 - 2010 Global Competitiveness Report, a biannual report published by the World Economic Forum.  There are many elements that contribute to a country's competitiveness, but the Forum puts a lot of emphasis, as it should, on innovation capacity. If innovation capacity were the only factor, the U.S. probably would not make it to the top 20.

There are many elements that contribute to a country's competitiveness, but the Forum puts a lot of emphasis, as it should, on innovation capacity. If innovation capacity were the only factor, the U.S. probably would not make it to the top 20.

Why? Because other countries are putting far more emphasis on innovation and entrepreneurship than the U.S. right now. In fact, "North America" is the only continent that is less focused on innovation now than it was in the year 2000 - and it's not Canada that's pulling the continent down.

In the meantime, everyone is asking 'where are the jobs?' Manufacturing has left the area. The jobs are where the innovation is - 50 percent of new jobs come from new companies within their first five years of establishment. New companies are established to monetize innovation.

Where is innovation? Are we blighted with rusty spring disease in the U.S.? As it happens, no. You see there are millions of potential jobs being held captive by the U.S. Patent Office in the form of patent applications that have no one to read them and not enough people to evaluate them because some are too technologically sophisticated for the patent examiners.

And the new Director of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), former IBM chief David Kappos, admits all this himself. He volunteers this information, because without more funds his office cannot function. Though the office was set up to be self-sustaining, surviving from its fees, billions of dollars were siphoned off and re-diverted by Congressional earmarking between 1992 and 2004, which really put the Patent Office behind in its application reviews. And things have gotten worse.

Just this past December, a budget provision that was to provide an extra $100 million to the USPTO was pulled at the last minute. Now, the office has a cap on spending which prevents it from hiring new examiners even if an examiner leaves his or her position.

All that leaves the Patent Office with 1.2 million new applications, three times more than there were 10 years ago, and 700,000 of them have not been picked up for a preliminary examination.

It's been the Patent Office that has helped create millions and millions of jobs for more than 200 years. Patents created jobs during the Industrial Revolution and patents need to continue to create jobs in the digital and biotechnology age.

Technology: A Gift That Keeps On Giving: via BruceClay.com

"Hundreds of thousands of groundbreaking innovations that are sitting on the shelf literally waiting to be examined - jobs not being created, lifesaving drugs not going to the marketplace, companies not being funded, businesses not being formed - there's really not any good news in any of this," Kappos said during a panel discussion at the annual trade show of the Biotechnology Industry Organization.

IPBiz’s Ebert: Kinsella Way Off on Patent Reform

Since Patent Reform is in the air, here is an older exchange with patent attorney Lawrence Ebert at the IPBiz blog that I just came across while binging. I mean, googling:

***

Kinsella way off on patent reform

December 14, 2007

Stephan Kinsella has a particularly insipid piece on patent reform, titled Another Reason to Reform Patent Law: Touch Off A Recession!

Kinsella writes: There’s increasingly hyperbolic opposition to patent reform efforts. Dude, some of us have been pointing to the “same old, same old” bad aspects of patent reform for years but guys like yourself never respond.

LBE published “Patent Reform 2005: Can you hear me, Major Tom?” back in 2005 and talked about it on IPBiz.

Kinsella finds boogeymen in the patent bar, just as Jaffe and Lerner do:

Naturally, the organized patent bar and intellectual property (IP) advocates have an interest in labeling recent developments “radical” so that any really radical proposals will be dismissed out of hand. (Patent lawyers also seem loath to have to learn some new rules—those CLE courses are so bothersome.)

Lots of people in the “organized patent bar” favor post-grant opposition, a current part of the house and senate patent reform packages. It creates MORE opportunities for patent lawyers. Duh, where’s your brain Steve? Oh, yes, lots of new rules to learn in post-grant opposition.

The changes to the rules on continuing applications were supposed to impact the backlog, but they will affect only 5% (or fewer) of filed cases. Tough to see how all this added paperwork is going to reduce backlog. Where’s your logic Steve?

Steve writes:

Well, I disagree that the proposed and recent changes are radical. Patent terms have not been shortened. The scope of what is patentable has not shrunk.Steve doesn’t mention that the ability to claim an invention will have shrunk if the new rules go into effect, and the ability to argue with examiners about stupid rejections will diminish. If a large fraction of continuing applications were devious attempts to claim the products of competitors, one might at least understand the motivation (if not the ultimate rationale), but the most abundant continuing application form is the RCE, wherein one can’t change the invention. One is arguing with the examiner about the claim scope of already submitted claims.

See also, PatentHawk Compact Prosecution and the 271 blog (Study Shows USPTO Backlog Is Tied More to Non-Final Actions, and Not Continuations)

No Hurry to End Patent Application Backlog

January 25, 2011

“No country grants more patents for inventions than the United States,” President Obama said in promoting confidence that our economy will recover.The remark, included in his third annual State of the Union address, however sheds light on a government failure that has transcended administrations of both parties for at least two decades.

The backlog of applications sitting in a Northern Virginia warehouse belonging to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is 1.2 million and growing. What once took 18 months to grant now takes almost four years. In today’s dynamics that can be “forever.”

In 1991, the financial burden of granting patents was shifted from taxpayers to the applicants through user fees. As the number of patent applications grew, the office was actually being run at a profit. (Sounds like a “Tea Bagger” success story, so far.)

Then Congress began to raid the patent office piggy bank to the tune of $650 million by 2004. As the number of applications expanded, USPTO did not have the funds to keep pace with patent examiners.

The American dream is to invent the 100 miles per gallon carburetor, the next smart phone, even a diet that really works. The patent helps prevent anyone else from stealing your design and keeping you from making the maximum return on your efforts.

Some economists maintain more jobs will be created by smoothing the path to innovation than by reducing government impediments. Lengthen time to review a patent application will increase chances to steal the idea. Raising money also becomes more difficult. Venture capitalists are not likely to contribute money to an invention that may never get out of the starting gate or has been stolen.

The job of patent examiner grows not only by the number of applications, but also patents already granted. In the 145 years from its founding in 1790, USPTO issued its first two million patents. Beginning in 1935 USPTO granted its second two million in the next 41 years. All the many more issued patents an examiner has to check against the application he is working on.

USPTO says 2,900 new examiners are needed over the next five years, adding to the current workforce of 3,500. A plan approved by the House and awaiting Senate action promises to no longer raid the USPTO piggy bank and would boost fees by 20 per cent to hire 1,500 new examiners over five years.

There is little doubt that as long as the patent process is slowed, less new jobs will be created by the lack of protected innovation.

If you are an unemployed engineer you can still find a job in China. According to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, since the entire backlog of applications is on the Internet, engineers sift through them to determine what intellectual property is worth stealing.

All of this could lead to the following conclusion:

We are only just beginning to learn how both parties have manipulated foreign policy at the expense of American jobs. What if the patent processing backlog was part of the same program?

Ambassador Jones tells the Sultan of Siam:

“I’ll tell our people that we asked and you agreed to crack down on intellectual property theft, but then we’ll keep the backlog of patents going so you can steal more of our inventions.”

Wink. Wink.

Patents Pending: IP Attorneys Advise Clients on Longer Process

Wisconsin Law JournalOctober 26, 2009

The next Thomas Edison or Bill Gates may take a little longer to get discovered, if at all.

Intellectual property attorneys are enduring an increasingly arduous patent process on behalf of their clients, coupled with a backlog of approximately 1 million applications at the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

As a result, some inventors are reconsidering or even abandoning applications because they can’t afford a series of appeals or have simply grown impatient with the system.

“For the first time ever, clients are saying, ‘I just can’t put any more time and money into this invention. It’s just not worth it,’” said IP attorney Keith M. Baxter of Boyle Fredrickson SC in Milwaukee.

He said most clients accept the fact that the process will be relatively rigorous, and “nobody gets patents on fads.” But even before the recession hit, the timeline between filing an application and receiving a first office action or response from the Patent Office had begun to widen.

And the situation has gotten worse.

Baxter, who deals primarily with clients in the technology field, said that patents which previously had seen first office action in six months are taking three or four times as long. He suggested this could be a product of examiners granting a high volume of applications in recent years — and now the Patent Office is looking at them with more scrutiny.

“It could be too many patents getting through,” he said. “[For me] it may mean people with simple mechanical cases just get rejected.”

Michael Best & Friedrich attorney Thomas J. Otterlee said smaller inventors, especially, are concerned about the length of the process.

“When I tell them it can take, two, three or four years, they are a little surprised,” said Otterlee, who deals with mechanical devices. “Every time we respond to an office action, they ask ‘When is this going to end?’”

Timeline hard to predict

Otterlee said it is increasingly common for inventors to have to file several responses with the examiners at the Patent Office, and because it’s also taking longer to initially hear back, attorneys are having a hard time giving clients an accurate timetable.

Quarles & Brady patent attorney Jean C. Baker, who has 20 years experience, said that it’s particularly difficult for someone just starting out to have an accurate expectation of how long the process will take.

“We have attorneys here that filed applications years before they started seeing office actions,” she noted.

Baker also attributed the lengthier process to more complex applications, especially in the technology industry, and increased back and forth among patent examiners.

“They [examiners] are getting different things to look at than 10 years ago,” she said.

That may be why examiners appear to be less confident in granting applications and there always seems to be a lot of “double-checking.”

“There are more situations where people agree to something on the phone, then change their minds because they go up the chain and someone else disagrees with them,” Baker said.

In those cases, inventors often have to file a continuance or appeal the decision, which means an additional cost.

“That’s another filing fee, another office action and more lawyers’ fees,” Baker said. “You can easily add $3,000 to the process just because an examiner wanted to clarify something you had an interview about.”

But despite the hassles, attorneys say they haven’t noticed a significant dip in the number of clients seeking patent protection. In fact, while some clients are abandoning the process, Baxter said that given what can be riding on approval, other clients may be more willing to fight than in the past.

“In my first 15 years I probably had two cases in appeal, and now I have five or six … because people are just not getting what they believe should be allowed through,” he said.

Congress Takes Up Major Overhaul of Patent Law

The Associated PressMarch 3, 2011

The patent system hasn't changed much since 1952 when Sony was coming out with its first pocket-size transistor radio, and bar codes and Mr. Potato Head were among the inventions patented. Now, after years of trying, Congress may be about to do something about that.

The Senate is taking up the Patent Reform Act, which would significantly overhaul a 1952 law and, supporters say, bring the patent system in line with 21st century technology of biogenetics and artificial intelligence. Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, hails it as "an important step toward maintaining our global competitive edge."

Senate backs USPTO receiving all fees

A first step to strengthen the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office was taken this week when the USPTO would gain power over the revenue it collects under an amendment the Senate approved. It’s a step seen as critical to reducing the lengthy backlog in processing patent applications.

The Senate measure would end the practice of diverting fees paid to the patent office to other government programs. It came as an amendment to legislation that would carry out the first major overhaul of the patentsystem in almost 60 years.

Sen. Tom Coburn, R-Okla., who promoted the amendment, said that last year some $53 million in application and other fees paid to the patent office was spent elsewhere.

The provision, which also allows the office to set its own fees, aims to rectify a backlog: 700,000 applications are awaiting initial action, and it takes three years to get a patent request granted.

The overall bill, which is expected to pass this week, would also carry out fundamental changes in howpatents are processed. Instead of the current system where patents are given to the first to invent, the United States would adapt the system used by all other industrialized nations, where they go to the first to file.

The White House, which supports the bill, said the first-to-file system would simplify the process of acquiringpatent rights, reduce legal costs, improve fairness and support U.S. innovators.

The switch has been opposed by independent inventors and smaller companies concerned that they wouldn't have the resources to compete with corporate competitors, but Patent and Trade Office Director David Kappos told reporters Tuesday that the transition comes with increased legal certainty to assure that smaller businesses would not be disadvantaged.

"First-inventor-to-file is a win for all American innovators, of all sizes and all industries," Kappos said.

Kappos also welcomed provisions giving his office more control over fees, saying it would allow the office to hire more qualified examiners and upgrade its technology, resulting in the issuing of higher-quality patents in a faster period of time.

Prospects for bill passage seem good

Congress has been trying for well over a decade to rewrite patent law, only to be thwarted by the many interested parties - multinational corporations and small-scale inventors, pharmaceuticals and Silicon Valley companies - pulling in different directions. Prospects for passing a bill now, however, are promising.

The Senate bill is sponsored by Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., Hatch and another top Republican on the panel, Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa. The committee voted 15-0 in early February to send the legislation to the full Senate.

The overhaul is long overdue. It now takes the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office about three years to process a patent application. There are about 1.2 million applications pending - 700,000 waiting consideration and another 500,000 somewhere in the process. The patent office says it received about 483,000 applications in 2009 and granted about 192,000 patents.

"Hundreds of thousands of patent applications are stalled" at the patent office, Leahy said. "Among those is the application for the next great invention."

The most sweeping, and controversial, change is the transition from a first-to-invent application system to a first-to-file system that is used by every other industrialized nation, but has been opposed by independent inventors. It comes with an enhanced grace period to protect inventors who publicly disclose their inventions before seeking patents.

Companies or individuals seeking patents in multiple countries are confronted by a different set of rules in this country, said Bill Mashek of Coalition for 21st Century Patent Reform, a group that represents big companies like General Electric, Pfizer and 3M.

"It puts us at a disadvantage globally."

The bill would create a nine-month "first window" post-grant procedure to allow challenges to patents that should not have been issued and to cut down on litigation and harassment of patent owners by improving the review system for challenges. It provides more certainty to damage calculations.

It also gives the patent office authority to set its own fees at a level that will give it enough funds to reduce its backlog of applications. It requires that smaller businesses continue to get a 50 percent reduction in fees and creates a new "micro-entity" class - with a 75 percent reduction - for independent inventors who have not been named on five or more previously filed applications and have gross incomes not exceeding 2.5 times the average. The standard fee for filing a patent is now $1,090, with additional maintenance fees over the life of the patent.

In a change from current law, tax strategies could not be patented.

A variety of backers

Leahy's office lists a diverse group of supporters, including major drug companies, IBM, the AFL-CIO, the Association of American Universities, Caterpillar and USPIRG.

One reason supporters are optimistic about the bill's prospects this year is that courts have dealt with some of the more contentious issues involving lawsuits and damage awards.

"When we started these efforts many years ago, we faced a grim landscape where patent lawsuits threatened to stifle the pace of innovation and shut down our factories," David Simon, associate general counsel for Intel Corp., told the House Judiciary Committee. "Today, the scenario has changed drastically."

Testifying in February on behalf of the Coalition for Patent Fairness, a group of high-tech companies, Simon credited the change to Supreme Court and other federal court rulings dealing with such practices as venue shopping where litigants sued in courts known for handing out large damage awards.

Simon's coalition, however, has not endorsed the Senate bill. In a statement, it said the bill still needs to do more "to lessen the growing burden of abusive and unjustified patent infringement claims."

A group of nine organizations representing small businesses, start-ups and independent inventors was more forthright in its opposition, saying in a letter to senators that the first-to-file system would have "unique adverse effects" on its constituents.

"The bill favors multinational and foreign firms over start-up firms seeking an initial foothold in U.S. domestic markets, and favors market incumbents over new entrants with disruptive new technologies," said the letter signed by groups such as American Innovators for Patent Reform and the U.S. Business and Industry Council.

USPTO Seeks to Rehire Limited Number of Former Examiners

PatentLYO.com

December 26, 2009

The USPTO has had a fairly large attrition rate over the past 15 years. Part of the cause of the attrition has been within USPTO. However, I believe that the real driving forces have been (1) the private great demand during that time for patent law professionals; and (2) the fact that many of the USPTO new hires were young college graduates who expected to leave their first job within a couple of years.

Training of replacement examiners is slow and expensive and also frustrates patent applicants who expect a professional examination for their $1000+ fee.

Now that the private law market has shifted, the USPTO now sees its opportunity to hire experienced individuals — folks who will “hit the ground running” and who will likely be more stable in their life goals. As a first step, the USPTO is “reaching out to former patent examiners, inviting them to return to the agency.”

In a media quote, USPTO Director David Kappos said:

“These examiners can have an immediate impact on the patent examination backlog and reducing the backlog is our top priority.”

The immediate limited program is focused on former examiners who passed their probationary requirements and who resigned less than three years ago or have more than three years experience examining patents. See www.USAJobs.gov (GS 9–14).

U.S. Patent Office Needs Money to Reduce Backlog: Obama

The China PostJuly 15, 2010

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office should get as much as US$279 million to help the agency deal with a backlog of patent applications, U.S. President Barack Obama said in a request for supplemental funding from Congress.

The patent office, which experienced a drop in fees last year because of the recession, is seeing a rebound in applications and wants to keep more of the money it collects. Otherwise, any money above its US$1.89 billion fiscal 2010 budget would enter the general treasury to be spent by Congress on other programs.

Improving the patent office has been a key goal of the Obama administration, which has said that better protection for intellectual property will be a driver of economic growth. The patent office has said technology innovation is linked to three-quarters of U.S. growth since the end of World War II.

The additional funds would go toward salaries and expenses directed at improving efficiency at the agency. The patent office is struggling to reduce a backlog of more than 700,000 applications in the last fiscal year. On average, it takes 34.6 months to complete a patent application and the office is seeking to reduce that to 20 months by fiscal 2014.

The proposal would “support efforts to reduce backlogs in processing patent applications — by spurring innovation and reforming U.S. Patent and Trademark Office operations to make them more effective,” Obama said in a letter yesterday to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a California Democrat.

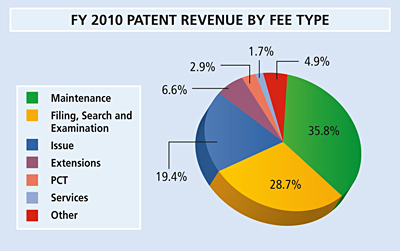

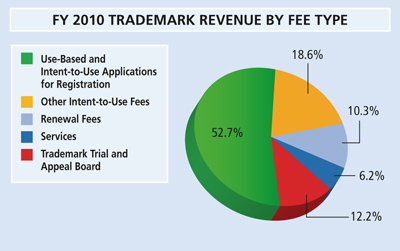

The agency is funded exclusively by user fees collected from initial applications and to maintain the status of issued patents, with a smaller part of the agency's budget coming from trademark-related fees. In a May 10 Congressional hearing, patent office Director David Kappos said the agency projects it will collect US$146 million to US$232 million more than is appropriated in the current fiscal year.

Under Obama's proposal, which must be approved by Congress, the agency would get US$129 million that had been budgeted for the Census Bureau and be allowed to keep as much as US$150 million above that if it collects more in fees, for a total budget of US$2.17 billion in fiscal 2010.

Obama has proposed a US$2.32 billion budget for the year beginning in October. The agency plans to hire 1,000 patent examiners in each of the next two fiscal years to reach its goal of reducing the application pendency rate.

Kappos, a former International Business Machines Corp. assistant general counsel who became head of the patent office a year ago, has been trying new programs to speed the process of reviewing patent applications.

Innovation Crisis: Job Creation Stalled by Patent Backlog, Says Pat Choate

By Stacy Curtin, Finance.Yahoo.comSeptember 8, 2010

Today President Obama is widely expected to reveal more of his plan to help revive the economy. In addition to the $50 billion infrastructure program announced Monday, the President will likely call for the following:

- $200 billion in tax breaks for business investment in new plants and equipment

- $100 billion to extend the research and development tax cut

But, many economists feel the President’s proposals are too little, too late.

Growth equals jobs and growth in this country is stagnant: GDP has slowed to less than 2% for the last few quarters and nearly 15 million people are unemployed -- according to the "official" tally. Millions of Americans have either lost their homes or are saddled with under water mortgages.

There is another - less talked about - factor stifling job growth says Pat Choate, author of “Dangerous Business” and “Saving Capitalism.”

The U.S. Patent Office is broken

There is a backlog of 1.2 million patents waiting for approval, Choate notes. "Patents are the basis for most innovation. People will not invest in new technology unless they can have a long period of exclusive use so that they can get their money back."

If innovation is at risk, it also prevents business from spending and creating new jobs.

"The value of patents, copyrights and trademarks, which is called intellectual property, now makes up almost 80% of the total value of U.S. corporations,” says Choate. "I say the greatest store-house of unused, cutting-edge technology in the world are the patent office warehouses in Northern Virginia."

Many technologies "go obsolete" while waiting for approval, he tells Aaron in this clip. Meanwhile, many big companies use what's know as "efficient infringement," which is a fancy way of saying they calculate the benefits of stealing someone else's patents vs. the possibility of getting caught, tried in court and being forced to pay damages and penalties, Choate says. (This "strategy" may explain the rash of patent infringement suits in the tech sector such as between Apple-HTC, Intel-AMD and NTP vs. everybody.)

"The Patent Office granted Alexander Graham Bell's patent for the telephone three weeks after he submitted his application," Choate says. "Today, the Patent Office has such a backlog that it takes three years from the time an application is submitted until it is approved or rejected."

If President Obama’s tax credit for research and development actually spurs economic activity, will our new innovations stall in the three-year backlog at the U.S. Patent Office?

"As a country, this is very foolish," Choate says. "Spend another $1 billion, hire [more] patent examiners, make a patent cheap, do it quickly, and let’s get on with the innovation that we need for job creation in this country."

Innovation Crisis: Job Creation Stalled by Patent Backlog, Says Pat Choate

Comment by Jose, Finance.Yahoo.comSeptember 8, 2010

When was the last time Steve Jobs was a "small inventor"? Steve himself has never denied having copied others ("steal"), most notably Xerox. Of course, this guy talking did not in fact say that with a straight face if you watch closely.

Bill Gates, another "small inventor", is famously quoted as talking about how stifling software patents would have been if exploited last century; however, Microsoft, afterward, having reached monopoly status, started using patents as an anti-competitive weapon. Today, Bill Gates loves investing in patents. [Once a monopolist, always a monopolist.] Patents are used to protect the existing giants much more than they are used to help any small firm.

Patents are a tax on consumers and on the majority of inventors and producers. Patents lead to industries that shrivel. Software does not need patents. Genes do not need patents (other people own my body!) And most industries would gain from reworking the entire patent monopoly system, preferably by dropping the stifling "monopoly" part.

Today, life moves much faster than it did in 1790. Today we "need" 20 years of monopoly? I don't think so.

The principle problem is the monopolies. The long MONOPOLIES on broad relatively easy ideas are the PROBLEM.

Listen, where would physics, math, music, literature, etc, be if we had had patents in those areas? It's virtually impossible to make a great product without leveraging the geniuses and smart people of the past 20 years.

Software inventions are virtual. They are mathematics combined with fiction in most cases. Mother nature does not pose limits or hide information from software inventions as is the case for every form of tangible invention. Manufacturing and distributing each new unit copy of a software product is $0 in time and money -- just check out all the software being produced this way. This means we have many many participating inventors (low bar to participate and recoup costs) who are hand-cuffed with every single software monopoly out there.

Monopolists love software patents because they fear small firms and the great work being done and given away for free by many very smart individuals working together. You give a little away, but you gain a ship load being contributed by others. It's efficient advancement, highly exciting to those participating, very cheap for everyone, promotes small businesses (great for VCs and for most workers), and promotes those that don't require monopoly profits. If this nation was run by a small number of monopolists, very little would get done and most money would be in the hands of a very few at the top. Consumer products would stink.

U.S. Patent Office Grants Massively More Patents Than Ever Before

By TechDirt.comJanuary 18, 2011

Commerce Secretary Gary Locke has made it clear that he wanted to US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to clear out some of the backlog on patents, and it quickly became clear early last year that the way the USPTO was doing this was by simply approving more patents while giving less scrutiny to the patents in question -- meaning that we're now getting a ton of bad patents approved. It seemed like an obviously bad sign when we passed the total number of patents approved in 2009 by October of 2010.

Now the final numbers are in: nearly 220,000 patents granted (219,614 if you want to be exact), a massive 31% increase over 2009 and still significantly more than ever before in history. The highest previous year was 2006, when a mere 173,772 patents were granted. So this is still 27% more patents granted in a single year than ever before. I find it hard to believe -- as USPTO supporters claim -- that the Patent Office suddenly figured out how to approve 30% more patents without decreasing the quality. Patently-O put together this lovely chart to demonstrate the pattern:

If you look at the numbers over the past thirty years, you see that massive jump in 1998 and heading on up until 2003, when the Supreme Court finally realized that the patent system was massively out of control and was doing a lot more to harm innovation than to help it. However, over the last few years, in response to pressure from those who abuse the patent system to squeeze money out of others, it appears we haven't just reverted to the way things were before, we've leapfrogged the trend line. I can think of no better way to massively slow down American innovation than this. What a shame. Kappos' legacy is going to be a pretty sad one when all is said and done. It's really too bad. When he was first put into the job, it appeared he actually understood how bad patents could be harmful.

And, it should be clear that it's not just the small "trolls" that are the issue here. A ton of big companies stocked up on tons of new patents. Not surprisingly, the top patent getters are companies that are heavily involved in massive value-destroying patent thicket lawsuits: IBM, Samsung and Microsoft. Apple -- which has gone all in on some patent battles -- received nearly twice as many patents in 2010 as in 2009. Ditto with Qualcomm.

Oh yeah, and guess which area of technology had the highest number of new patents? "Multiplex Communications." In other words, the mobile phone patent thicket of lawsuits we've discussed in the past is only going to get messier:

Patent Backlog Is Clogging Job Growth

By Nathaniel Cahners Hindman, The Huffington PostSeptember 10, 2010

The greatest stockpile of unused, cutting-edge technology in the world is sitting in a warehouse in Northern Virginia gathering dust, author Pat Choate told Yahoo Finance Wednesday morning. The warehouse, Choate said, belongs to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and the stockpile is a backlog of 1.2 million unexamined patent applications.

A number of analysts claim that unclogging this patent build-up at the USPTO -- by ending a diversion of funds that has left the agency underfinanced -- could jump-start job creation in America.

Henry R. Notthaft calls the patent office the "biggest job creator you never heard of" in a recent Harvard Business Review article.

"It is [the USPTO], after all, that issues the patents that technology startups and other small businesses need to attract venture capital to pay salaries," says Nothhaft in a separate New York Times op-ed.Increased funding at the patent office will reduce delays and result in the issuance of more patents. Nothhaft insists that this will lead to more innovation and more jobs.

But since 1992, Congress has diverted more than $750 million in patent fees from the USPTO to other purposes. Without the money, the agency hasn't had the resources to deal with the threefold increase in patent applications over the past 20 years. Today it takes an average of over three years for inventors to get a decision on a patent, which is at least twice as long the average wait time 15 years ago.

"Hundreds of thousands of groundbreaking innovations are sitting on the shelf literally waiting to be examined," David Kappos, Director of the USPTO, told an audience at a biotechnology conference earlier this year. "[This results in] jobs not being created, life-saving drugs not going to the marketplace, companies not being funded, businesses not being formed," Kappos added.

And while many say patents spur entrepreneurship because they give inventors a stronger incentive to invent, and offer venture capitalists more reason to open their wallets -- others disagree entirely.

Patents, they argue, do not increase incentives to invent, and are not vital to startups getting financing. In fact, they can harm innovation because they breed intellectual property battles that stall billion-dollar innovations over patents worth far less. Often these legal battles are between large technology firms and so-called "patent trolls" -- firms that buy up patents with the sole intention of shaking down large companies that allegedly infringe on them. As the Economist notes, a group recently found that these types of cases have risen from 109 in 2001 to 470 in 2009.

As the flood of patent-marking lawsuits continues to flow, and the debate spills into Congress, legislation to fix America's broken patent system remains tied up in the Senate.Director's Forum: David Kappos' Public Blog

www.uspto.govJanuary 3, 2011

Improving Key Patent Processes and Sub-processes

As the Patents organization moves toward its goal of reducing the average total pendency of patent applications to 20 months by 2015, it is important to streamline all components of the examination process. Everyone plays a role – including of course our examiners and our quality assurance professionals and our searchers and our management team, as well as all of our support functions and our Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences and Central Reexamination Unit. The technical support staff plays a crucial role in this effort. And they are making substantial progress. I’d like to highlight areas where our technical support team is achieving real results.

In FY 2010 the Technology Center Technical Support Staff of 274 legal instrument examiners and legal document review clerks:

- Entered more than 2.9 million documents;

- Verified more than 264,000 allowed patent applications;

- Reviewed and counted over 2,300,000 office actions; and

- Processed more than 257,000 new patent applications.

These stats represented all-time records for the USPTO, reflecting all-time record workflow through the Agency including interviews conducted, office actions processed, notices of allowance, and final rejections.

An example of the incredible effort put forth by our technical support staff is the reduction of amendment entry times over the 2009 fiscal year. At the end of FY 2009, the backlog of documents to be entered was over 170,000 and the average amendment entry time was 34.5 days. Not good at all. In response, the head supervisory legal instrument examiners reengineered the work distribution process to better balance workflow, and to ensure that all documents were entered in date order.

As a result of their determined reengineering efforts, as of October 2010 the backlog of documents was reduced to about 15,000, with amendments being entered in 5.2 days on average. Additionally, the backlog of new applications to be processed was reduced from over 100,000 in FY 2009 to just 13,000 as of October 2010.

These are, quite simply, jaw-dropping improvements. And to top off the performance, the team engineered this dramatic reduction in the backlog of documents to be entered while at the same time maintaining the timeliness of other critical areas of their work processes. Really excellent.

A second example: Our post-examination technical support team has recently begun to focus on its cycle times. It faces the unique challenge of handling the increased rate of patent issuances coming through as we work off our backlog of unexamined patent applications.

So just to keep pace, this team had to handle an increase of some 40,000 utility patents issuing in FY 2010 over FY2009. Building on successful process improvement efforts in the printer rush area from early in FY10 (printer rushes occur when an application has been allowed by the examiner, but a technical issue like claim renumbering causes the application to drop out of the issuance queue, requiring attention by technical support staff), the post-examination program analysts and quality control specialists established electronic upload and automated tracking of printer rush queries.

As a means of reducing paper-based and e-mail inefficiencies, the team also improved its automation capability so that the post-examination applicant service representatives were able to immediately enter applicant's application data to facilitate issuance.

Here are the results so far from this effort:

- For FY 2009, the average time from applicant's issue fee payment to issuance was 50 calendar days for 165,212 applications.

- For FY 2010, the average time from applicant's issue fee payment to issuance was 51 calendar days for 207,915.

- For FY 2011 to-date, the average time from applicant's issue fee payment to issuance is running at 43 calendar days for 39,064 applications.

This is an impressive eight-day (better than 15 percent) improvement in cycle time in less than one quarter. While there is more to do, the technical support team is again showing that it can achieve excellent results in cutting its processing times at USPTO.

So whether you are a USPTO employee, or a patent applicant, or a member of the patent bar prosecuting applications in front of the Agency, if you’ve been noticing processing times speeding up, now you know who is making that happen behind the scenes: our outstanding technical support staff.

I would like to thank and recognize the technical support staff – of course for the Patents organization but also throughout the USPTO -- for your hard work and dedication, and most importantly for your clear, measurable accomplishments. Reducing pendency is a challenging goal, requiring team effort among all employees playing a role in patent application processing. The technical support staff’s contributions are vital to our Agency putting Americans to work, putting new products and services into the marketplace, and creating opportunity for our country and for the world.

Patent Chief Kappos 'On the Hunt' to Reduce U.S. Backlog, Spur Innovation

By Susan DeckerSeptember 9, 2010

David Kappos, the head of the U.S. patent office, said his agency is “on the hunt” to cut its applications backlog to the lowest since 2007 to further President Barack Obama’s goal of job growth through innovation.

U.S. Patent and Trademark Office application reviews, which often take more than two years, have been sped up and hiring practices improved, Kappos, 49, said in an interview yesterday at Bloomberg’s Washington office. Kappos says the changes are part of efforts to help the U.S. maintain its economic power.

“I’m quite convinced there’s really only one way that will happen and it will be based on innovation,” said Kappos, who spent more than two decades as an engineer and intellectual property lawyer for International Business Machines Corp. “Innovation-driven companies, small and large, especially small, are huge creators of jobs and creators of wealth.”

Obama, who yesterday said he recognizes that the U.S. economic recovery has been “painfully slow,” has called for incentives to promote American ingenuity as part of his measures to create jobs and expand productivity. Patent applications are up about 4 percent for the year that ends this month, following a 2.3 percent drop in fiscal 2009, led by medical, computer, biotechnology and nanotechnology inventions, Kappos said.

“The U.S. business sector seems to be reviving,” Kappos said. “The recovery isn’t as fast as we’d like it to be, but one leading indicator is the filing of patent applications.”‘Locked Down’

Kappos said he has been working to improve the efficiency of the patent office and eliminate a backlog of applications that had reached 750,000.

“You can think of each one of these as a business, as some new product or service that’s sequestered in a government agency, that’s locked down, that’s inhibited from reaching the marketplace,” Kappos said. “To have 750,000 of these things sitting in a government agency is not good for innovation.”

In the 13 months he’s headed the agency, Kappos has worked to meet an interim goal of cutting the backlog to less than 700,000 by the end of this fiscal year. He said it would be the first time in three years that “the first significant digit of the USPTO’s backlog was anything other than a 7.” He said he wants to have an “inventory” of pending applications of 325,000 by 2015.

“We’re fans of his,” said Herb Wamsley, executive director of the Intellectual Property Owners Association, which represents companies including Intel Corp., Monsanto Co., Johnson & Johnson, and 3M Co. “He has been very energetic in creating a great many proposals and he’s very creative.”

Kappos had been vice president of the Washington-based group and was in line to be president before he was tapped by Commerce Secretary Gary Locke to head the patent office.

Candy and OvertimeObama has proposed a $2.32 billion budget for the agency in the year starting Oct. 1, with a 15 percent increase in fees to help pay for changes Kappos is making. The agency is funded by the fees it collects.

To reach his goals, Kappos said he is drawing from his time at IBM, the world’s largest computer-services provider, to introduce more “business-related processes” at the agency. He has changed how examiners process applications, with more personal interviews with inventors early in the process. The agency is holding pep rallies and approving overtime, and Kappos is handing out candy to improve morale and productivity.

“I’m just running business plays at the USPTO and so far no one’s told me you can’t do this,” Kappos said. “So I keep running the plays I learned from 26 years in the business sector.”Fast-Track Programs

There were 485,500 patent applications filed in fiscal 2009, and 190,121 patents issued, the most in the agency’s history. There were more patents issued in fiscal 2009 than applications filed in fiscal 1993, according to agency data.

Kappos created a special program that lets applicants with inventions that increase energy efficiency petition for a speedier review. The so-called green energy program has been so popular, a similar approach is being considered for other products including medical devices, Kappos said.

The agency also is developing a three-track system that would let applicants, for a fee, get their inventions reviewed in about a year. Kappos said he expects smaller businesses will take advantage of the program, which may begin in about a year.

Inventors of some medical devices may want fast processing, while drugmakers aren’t in a hurry because they’re also waiting on regulatory approval, Kappos said, likening the program to tiered pricing options by companies such as FedEx Corp.

“Not every package needs to go by ground delivery,” he said. “Some packages need to go by overnight, some packages ground delivery is fine, and some you say look I’ll just send it third-class, it’s bulk mail, it can take two weeks.”